What is leadership? Follow me, and you may or may not find out. The only thing I know for certain about leadership ability is that I don’t have it. But it’s worth considering the role of leadership in the firmament of democratic (or democracy-compatible) ideas. And we begin with two premises: one, leadership clearly isn’t confined to – and did not originate in – the democratic sphere. It began as tyranny, political or religious. Two, it’s not a major focus of study within the liberal arts, except perhaps in certain political science or political psychology courses.

I’ve seen examples of great leadership, both from afar and close-up, yet I still have trouble defining that slippery term. Every society needs leaders, because most human organizations require some forms of hierarchy, and we’re not all suited to be at the pinnacle. (That’s not to say that we don’t have some supremely unqualified and unfit leaders). I’ve seen leaders (mostly in the nonprofit sector) who are visionary planners; who make excellent staffing and policy decisions; who inspire their co-workers (and, let’s be honest, their underlings; armies need both privates and generals, and so do most organizations). I’ve seen great talkers and great orators – and weaker ones who nevertheless guide their organizations wisely and well.

What I’m suggesting is that leadership, like almost any concept that is interesting and complex, is a family-resemblance concept. It doesn’t consist of a fixed set of defining characteristics, which are co-present in all cases, but rather of multiple characteristics that exist in various permutations. If that seems obvious to you, go to the head of the class in Wittgenstein 101.

Hollywood, which plays an outsize role in our culture (not just when it comes to leadership) loves heroes and villains, and some heroes and villains are leaders. Most heroes are either leaders or outcasts. Most movies stress action, warfare, interpersonal drama; as Shakespeare said in “Troilus and Cressida,” “Things in motion sooner catch the eye/Than what stirs not.” Unlike Shakespeare, Hollywood seldom focuses on the moral and intellectual traits that leadership embraces. And it’s hard for film to capture how organizations or movements work, or how society writ large works. Film tends to personalize.

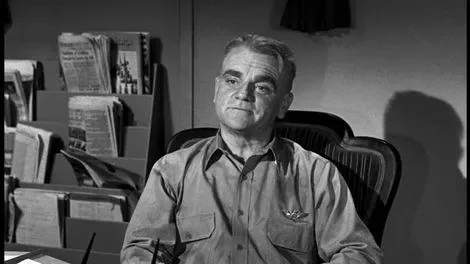

For all that, I recently re-discovered a great portrait of a leader – a quiet master class in how to manage people and organization toward a goal – in a 65-year-old World War II film: “The Gallant Hours,” from 1960, in which James Cagney played one of his greatest roles, starring as Vice Admiral William F. Halsey during the battle of Guadalcanal. The film was produced and directed by the actor Robert Montgomery, who also provided the uncredited narration.

Leadership is (not surprisingly) a nonrandom combination of human qualities, not a single quality. Firmness, decisiveness, tactical and strategic brilliance, the capacity to inspire. Integrity and character (although Gen. Douglas MacArthur showed it despite considerable pomposity). So we’re talking about varying blends of strategic brilliance, character, and charisma.

More specifically, I think leadership depends upon two crucial skills that are not always co-present in the same person. One is the ability to assess situations – in the world, or in a community, on a battlefield, in an organization or a movement – and make confident decisions, trusting one’s own judgment. Ulysses S. Grant comes immediately to mind. The other, perhaps equally crucial, is the ability to listen to and absorb the knowledge and wisdom of others. Halsey had that balance of traits. So, I suspect, have most successful military leaders.

Vice Admiral William F. “Bull” Halsey

Halsey was appointed commander of US naval forces in the Pacific in the fall of 1942, as the Allies were attempting to avoid a second military disaster (after the fall of Bataan) in less than a year. Under his command, the tide was turned on the island of Guadalcanal; American forces were able to hold Henderson Field, the airfield on the island, and the Japanese withdrew from the Solomon Islands. The cost was staggering: casualty figures vary based on how they are counted, but an accepted number for the Guadalcanal Campaign is 7,100 Allied losses from combat or disease.

“The Gallant Hours” focuses almost entirely on Halsey’s role, and Cagney is in virtually every scene in the movie. But unlike some other American military leaders, Halsey was modest and generous as well as decisive, thoughtful, and aware of his place in history. It’s a portrait of heroic leadership at its best: of daring decisions combined with discipline and determination, and love for his fellow officers and personnel. The devotion was reciprocated.

The record isn’t entirely unblemished. In December 1944, Typhoon Cobra struck the US Pacific Fleet off the Philippines, sinking three destroyers and killing 790 sailors. It came to be known as “Halsey’s Typhoon.” I can’t say with authority whether that was a blunder or bad luck or both, but it was awful.

Different types of organizations and circumstances obviously call for different skills. But what Halsey brought to his task – under the higher authority of Franklin D. Roosevelt and Admiral Ernest J. King – doesn’t just deserve to be remembered. In Cagney’s re-enactment in the quasi-documentary film, he models a blend of traits that all leaders can learn from. With the exceptions of Washington, Lincoln, and Grant, it’s hard to find comparable examples in our past of military brilliance and courage that saved America from even worse disasters.

Few people are born leaders, and even fewer develop the skills to lead; I suspect that it’s mostly hardwired. But recognizing leaders and leadership, and choosing accordingly, is part of democratic citizenship. It’s something we must do in various capacities: as students, voters, board members, historians, and as a society reckoning with its past.