The distance between Mt. Rainier, in Washington State, and Mt. Adams may not seem like a particularly important question. For reasons that I find inexplicable, you may not be dying to know the answer. It’s just something out there that doesn’t affect your life, or so you may suppose. But to me it’s vital, for reasons I’ll explain. Vital as in important, and vital as in life-giving.

I got lucky when I snapped this shot of the two great peaks – to me they are ineffably beautiful and majestic landforms. For one thing, they remind me of nature’s utter predominance over humankind and our need for humility in its presence (up to a point; I’ll get back to that in a minute). Second, they evoke the manifold beauties of the American landscape – something we can be proud of apart from (and despite) everything else, including those things that shame and embarrass some of us. Third, there’s the sheer joy of space, the intoxication of visible distance. A feast for the gluttonous eye.

When I took the picture, a year or so ago, I probably figured the two peaks were forty or fifty miles apart as the crow flies. I’m not from the Pacific Northwest (though I wish I were); and it’s hard to estimate distances based on a photograph or a view from the window of a jet plane. I wasn't far off: the summits of Rainier and Adams are 47 miles apart. I was thrilled that through the magic of flight (and if that sounds trite, I don’t care; it’s still magic) I could see that far. To put it in perspective, from peak to peak you’re looking across a distance equivalent to about a fiftieth of the span of the continental United States.

Views like this don’t make us feel small or insignificant, or not me anyway. Rather, they lift us, by fixing us in relation to space. Are we smaller than mountains? Objectively speaking, yes. But “small” is a relative concept of size that humans invented, not mountains. It’s almost meaningless in this context. I refuse to think of our “smallness” next to nature as in any way diminishing.

The same is true for the universe. Sure, it’s obviously enormous. But enormous in a way that shrinks us? No, thank you. We diminish ourselves by how we live and think, how we care or don’t care, how we affiliate with certain kinship and tribal groups and disaffiliate with those of others; we don’t need nature’s help in getting smaller. We diminish ourselves when we say that nature diminishes us. And we are only small in relation to each other, not in relation to some black hole so far across the universe that we can only theorize about it.

To be sure, not everyone finds land and water and space as enthralling I do. It’s a gift of sorts, but one you can go out there and help yourself to. You can also lead a rich life by knowing a lot about something – the Earth’s crust, or Jane Austen, or the Roman Republic – without giving a damn about geography. But it’s still all around you, making you not-small. And if schooling doesn’t provide a bare minimum of geographic knowledge along with civic knowledge, it isn’t schooling. It’s just a place where you’re kept busy at a desk along with other kids.

In short, I want to say that basic geographic knowledge is a form of citizenship. It’s knowing and caring where you are, and where other people are who share our planet. And what is more foundational to education, to locating ourselves in the world, than knowing where we are? How can we know where we are except in relation to where we are not – to other places where other people wonder about us and where we are?

And that’s just to speak in foundational terms, not in practical life terms. The “pure” sciences, such as physics, chemistry, biology, and geology, are crucial windows on nature. But subjects like geography, meteorology, health, nutrition, and sexuality affect our lives more directly and universally. One can get by pretty well without deep knowledge of the scientific building blocks of nature; regrettably, I have done it. In retrospect, I would have preferred to learn about those building blocks, ideally in a transdisciplinary study of basic scientific literacy. I’ve spent part of my long life trying to catch up or compensate for that.

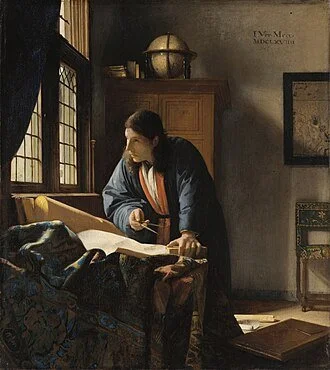

The Geographer, by Johannes Vermeer

Hopefully, some such broad-gauge approach will eventually appear in our schools, because we all need scientific literacy to function in the high-tech/AI/information age and whatever age comes next. Citizenship, and therefore the liberal arts, cannot leave nature out of the equation. Someday, we’ll all be citizens of the Earth.

Meanwhile, it may not help you to know where on the planet the most isolated human communities are, where the only species of freshwater sharks live, or which American state is crossed by the same river in two places more than a hundred miles apart. Or, for that matter, why part of Minnesota is stuck onto Canada, or why part of Delaware is on the wrong side of the Delaware River in what should be New Jersey. (Check any Rand McNally Road Atlas; and if such questions intrigue you, I recommend a book called How the States Got Their Shapes, by Mark Stein, which is also a streamable documentary series.)

But then again, maybe it just seems like it doesn’t help you to know about the places and occasions where nature hiccups or collides with human history. Maybe what we think we need to know is different from what we really need to know to be good citizens, parents, and neighbors. Maybe curiosity and fascination and love – of things and animals and people and land – are what really matter, what education should be all about. And there’s also room for awe.

Forty-seven miles from Rainier to Adams – wow.