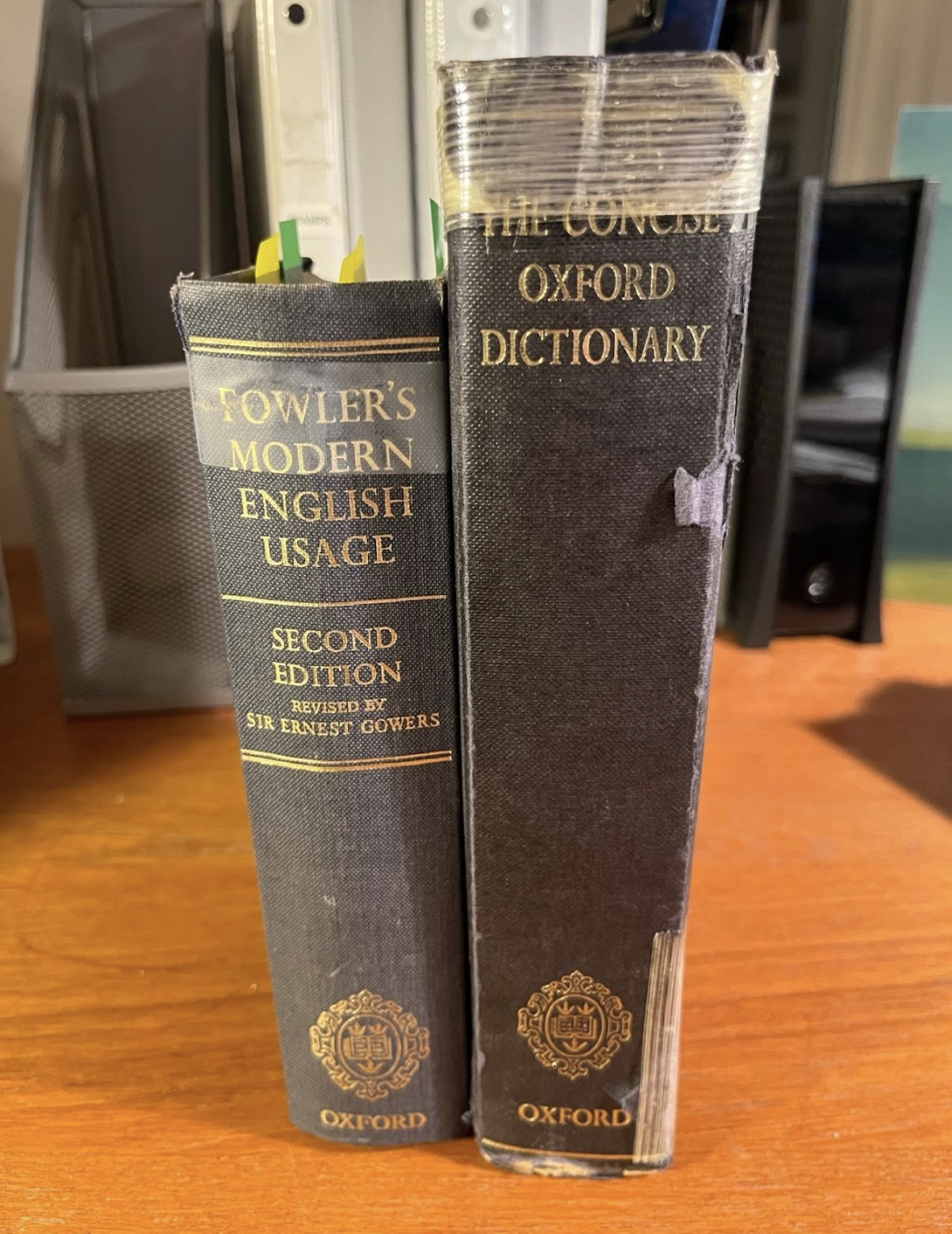

Two small, nearly matching books have stood on my desk for some fifty years, with my name, dating back to college, printed inside. One is the Concise Oxford Dictionary (6th edition). It is based on the 26-volume Oxford English Dictionary, and it looks like an ordinary-sized book. I was surprised to open the one-volume dictionary the other day and find that it contains 1,367 pages. The sixth edition, edited by J.B. Sykes in 1976, is based on the original First Edition edited by H.W. Fowler and his brother F.G. Fowler in 1911. And when I say “edited” in the latter case, I mean the Fowlers did all the work of assembling the dictionary. It took years.

I’ve consulted this book on a regular basis as a handy and authoritative guide to the spelling and meaning of English words. I also have the two-volume version of the O.E.D. in my office for more extensive etymological research; and for good measure, the leading American one-volume dictionary, Websters Third New International Dictionary. These are too large for my desk.

The second small volume on my desk is the mate of the first: Fowler’s Modern Usage, which comes in at just 725 pages and is slightly thinner than the Concise Oxford Dictionary. Fowler’s Modern Usage is a classic, and an industry standard or writers and editors. I must confess that I’ve opened it far less often than the Dictionary. It’s a bit more daunting, as it tells you how to write – what terms and phrases should be used, can be used, and should be avoided – and it’s more of a browser than a consulter. But just by opening it up, for example, you can learn that “filthy lucre” is a “hackneyed phrase,” i.e., one to be avoided. And that, presumably, was true in 1911.

My attention to these books – and to Fowler’s Modern Usage in particular – was spurred by an article in The New Yorker about Henry Fowler, written by Ben Yagoda. It gave me pause to realize how much we writers depend on other, smarter writers to tell us how to practice our craft. And I remembered that, though far from a great writer, I am a perfectionist by nature, and I suppose it’s because I like to get things right (and get them thoroughly) that I have, not just these two books on my desk, but an entire wall of reference books in my study. Simply put: I dig reference.

That shelf may be the closest thing I have to a functional autobiography. I won’t bore you with every title, but when I swivel my office chair and gaze at it, what stands out is the four-volume Encyclopedia of Philosophy (from the 1970s) edited by Paul Edwards. (As I recall, I acquired this and other great reference works, including the two-volume O.E.D., by joining and then quitting the Book-of-the-Month Club).

What’s this obsession with reference works all about? Maybe the ultimate thrill of it, if I can call it that, is their authority. The question I have may be narrow – what’s the definition of “incarnadine?” – but the answers are definite and, while not strictly speaking objective, at least they are authoritative, because humans write dictionaries and all dictionaries are not alike, they are seldom wrong or misleading. You come away fulfilled. But then, the realm of the objective is highly constricted. If we can’t agree that a triangle is objectively a three-sided figure, the world won’t stop, but our discussion will. Reference works can provide objective answers to questions like “what is a triangle?” and intersubjective (but bordering on objective) answers to “what is meant by ‘incarnadine’?”

Little thrills like these may not get you through the night. But they can get you through a paragraph that you’re reading or writing, which is almost as good. And while I’ve heard of something called the Internet, I’m thrilled to have almost an entire wall of my office reserved for reference books. It takes longer than Googling, but is vastly more satisfying.