In this, my third and (for now) final post about Ludwig Wittgenstein and the liberal arts, I’ll talk about one of his most important contributions to the philosophical study of language: the concept of “family resemblance.” And if ever a philosophical concept radiated relevance across the liberal arts, it’s this one.

First, a quick digression. While writing this post I received an eerily relevant text message: a video showing my son and his two-year-old daughter swimming in a pool, a continent away. It was a joyful scene; yet something about it struck me as peculiar. I’m not good at seeing family resemblance in relatives, my own or anyone else’s; yet I’ve often been told, and sometimes recognize, that my son looks like me. Too bad for him, but hardly extraordinary.

On this occasion, however, the similarity was jolting. I could almost believe I was watching myself splashing in the pool with my granddaughter. Maybe it was wishful thinking; but that epiphany is a timely entry point for this post, which is about family resemblance in a more general sense: the sense for which physical similarities among relatives provide an apt metaphor.

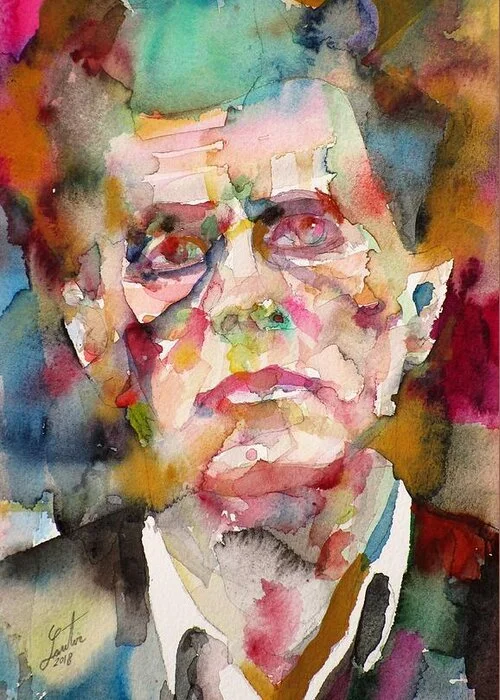

Like me, Wittgenstein happened to come from a large and complicated family. (That’s almost where our resemblance ends; traits of his that I don’t share include philosophical genius, scientific brilliance, sophisticated musicality, a deeply tortured psyche, lifelong spiritual suffering, and a profound social awkwardness that frequently manifested as rudeness or cruelty. Also, homosexuality, a trait he shared with several of his brothers; suicidality was another family trait, but one that thankfully he did not share. At least two and possibly three of his brothers took their own lives while young.) At every turn, Ludwig Wittgenstein’s life and psyche were as complex and absorbing as his thought.

Wittgenstein may not have been thinking of his own family when he propounded the idea of family resemblance in his magisterial posthumous Philosophical Investigations (1953, trans. G.E.M. Anscombe, P.M.S. Hacker, and Joachim Schulte; §65-67); but the concept is based on the model of familial similarity. It’s a rare case in the history of philosophy of a genuine conceptual breakthrough. And it isn’t very complicated.

The basic idea is as follows. Complex phenomena, such as “language,” or “society” or “politics” or “education,” cover a variety of things that are not all related in a single or obvious way. But they are related in partaking from a common pool of properties, even if any two given instances don’t share any one of those properties.

Wittgenstein’s example, famously, is that of a “game.” There are board games, card games, ball games, children’s games: not all are competitive, or have rules, or scoring, or demand physical or mental skills, or involve teams, and so forth. Yet we call them all “games” because they share family resemblances in their different blends of those various traits.

As Wittgenstein writes, “…the upshot of these considerations is: we see a complicated network of similarities overlapping and criss-crossing: similarities in the large and in the small.” Likewise, “the various resemblances between members of a family – build, features, colour of eyes, gait, temperament, and so on and so forth – overlap and criss-cross in the same way.”

The importance of this approach to analytic thinking is that it reveals unobvious connections, and the ways in which those connections can form complicated and irregular networks. Things may be indirectly related even without sharing any of the same properties. The concept of family resemblance thus expands our capacity to see how the world is, and is not, connected as the case may be. And that means more sophisticated analytic thinking – not just in philosophy, but wherever thinking takes place.

In 1995, the writer and semiotician Umberto Eco used Wittgenstein’s concept of family resemblance to dissect the concept of fascism. (I discussed Eco’s application of the idea in a recent blog post.) Eco uses family resemblance precisely as Wittgenstein intended, to show how different forms and historical instances of fascism differ but share from a common pool of traits; Eco identifies fourteen of them. And he explains the technique, perhaps better than Wittgenstein himself, as follows:

Consider four things that contain the various properties a, b, c, d, e, and f, in the following sequence:

abc bcd cde def

The first item (abc) contains none of the same features as the last one (def). But viewed in the aggregate, all four are all related in their different permutations of properties abcdef.

Some earlier writers had similar ideas, but didn’t work them through quite as far as Wittgenstein did. Oddly enough, the two examples I’m aware of were not philosophers. Ralph Waldo Emerson in his essay on “History” wrote that: “Nature is full of a sublime family likeness throughout her works, and delights in startling us with resemblances in the most unexpected quarters.” And Herman Melville implies the same thing, less directly, in Moby-Dick (Ch. 32) in his attempt to classify whales. One can also see a visual form of family resemblance in the Sean Scully painting “Backs and Fronts.” Great minds may not think alike – but sometimes they exhibit family resemblance.