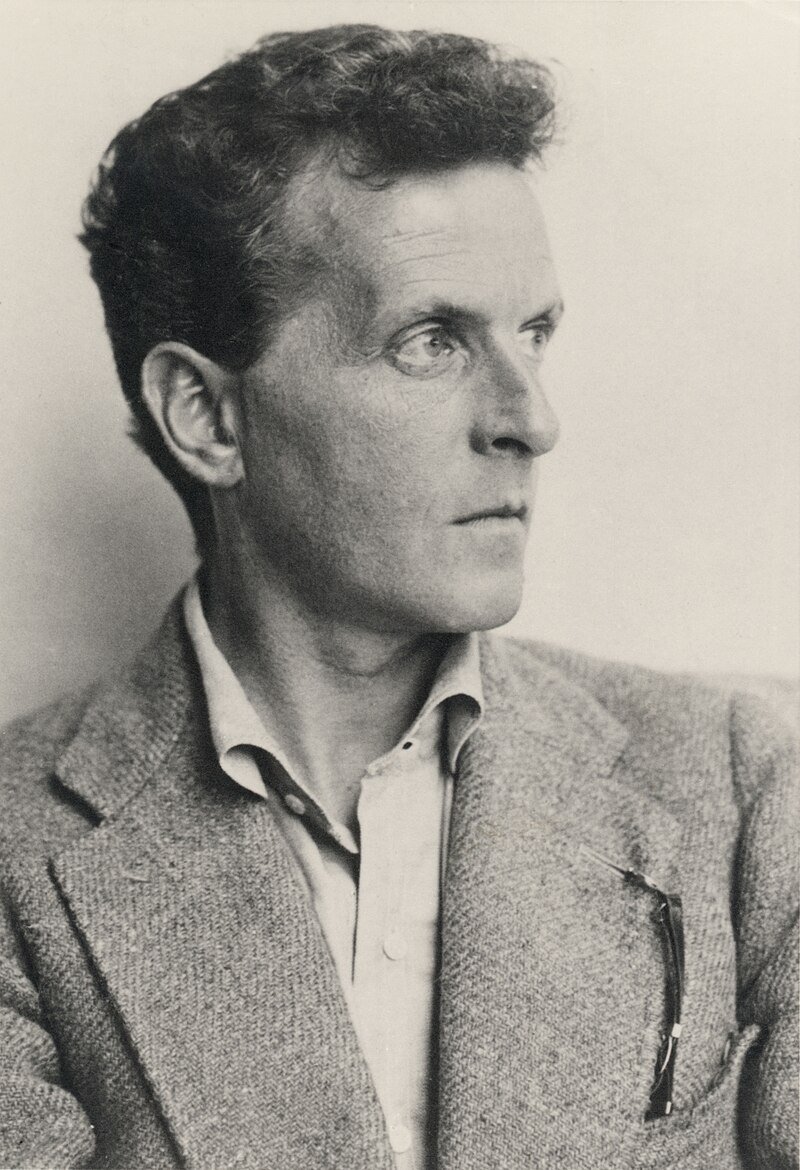

In my previous post, I introduced you to Ludwig Wittgenstein the man, with a thumbnail biography of his extraordinary life. In this post and the next one, we’ll talk in general terms about his thought and its enormous impact on philosophy in the 20th Century. That impact was mainly because of his focus on the very medium of philosophy: language itself.

Wittgenstein wasn’t the first thinker to study language, philosophically or otherwise. (It could be argued that any study of language in the semantic context, the context of meaning, is by definition philosophical). Thomas Hobbes wrote in The Leviathan (1651, Pt. 1, Ch. 4) that, “Words are wise men’s counters, they do but reckon with them; but they are the money of fools.” Words, Hobbes appears to be saying, should be used to measure and map the world, not to substitute for or be conflated with things in the world, such as objects, events, relations, actions or arguments. Individual words are not arguments; arguments are arguments.

Ferdinand de Saussure pioneered the study of linguistics in the late-19th and early-20th centuries; in Vienna, Karl Kraus and other intellectuals were practicing what they called Sprachkritik – the critique of language. Or, to put it another way, using language against itself as a kind of mirroring and clarifying exercise to reveal and expunge careless, incomplete, ambiguous, inaccurate, untruthful, deceptive, or manipulative, or otherwise imperfect language. Thus began the great 20th century project of focusing philosophy on what we say.

But it was Wittgenstein, in the Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus (1921) and later in posthumous works such as the Philosophical Investigations, who put language squarely on the table – as the main course, so to speak, of 20th Century philosophy. Kraus and others may have realized that all language is necessarily imperfect; and that is one reason – and reason enough – why philosophy couldn’t, as Wittgenstein supposed, be brought to a close.

We always need to expose the flawed or limited connections between words and ideas, and we need to use words to say different things that cannot all be said at the same time. And these are quintessentially philosophic tasks. Because we think mainly in words, we need to use (other) language to analyze our language, and to say with sentences what we can’t say with single words or phrases. Sifting and organizing and optimizing meaning is the basic philosophical enterprise that is performed across the liberal arts, and in everyday language as well. And it’s also known as rationality.

Two closely related ideas – among and perhaps above others – are significant in this great linguistic turn, and they become conditions of most subsequent thought in the Western world. One is the epistemological idea that we can grasp both the connections and the distinctions between language per se (the words we choose and how we arrange them) and the ideas or knowledge that language is designed to convey or represent. We can ask what exactly language does, how it does it, what its limitations are, and how they may be offset, with language as the only tool. There is a net gain in using words to consider how we use words.

The other, tandem idea has a quasi-moral, or at least imperatival, component. It’s the idea that language “itself,” as the consummate instrument of thought, though intimately bound up with forms of meaning – facts, analyses, descriptions, conjectures, factual or imagined narratives, arguments, and all manner of artistic expression – must be used self-consciously, must be navigated carefully, and must above all be subjected to critical scrutiny to see how it shapes (or misshapes) the ideas it purports to convey. That is to say, we must distinguish our language from its semantic business and explore how successfully, and at what cost, it conducts that business.

To appreciate this turn doesn’t require that we accept Wittgenstein’s early idea, in the Tractatus, that all philosophical problems are in effect bogus, mere linguistic confusions masquerading as something larger. (The very survival – and the occasional flourishing – of philosophy post-Wittgenstein, indeed thanks to Wittgenstein, refutes that notion.) But we do have to take language seriously, our own and everyone else’s, and keep it front and center whenever we think. And no one did more than Wittgenstein to establish that imperative.

In sum: words matter, as primary conveyors of meaning, and meanings are negotiable, debatable, and somewhat pliable. They variously carry logical, semantic, aesthetic, political, and moral weight. To parse meanings is to analyze and perforce, to do a kind of philosophy. It amounts to the critical and self-critical use of language, a combination of deeper awareness (and self-awareness) of both the power and shortcomings of words and sentences, and how we use language recursively to overcome its own opacity.

In doing that, across the spectrum of liberal learning, we create stronger foundations for our conversations as (inevitably partial and imperfect) exchanges of meaning. It is a core function not just of philosophy but of all critical inquiry.